How USAID Helped Shape Brazil’s Election

Part 3 of the Brazil Election Fraud Series

The Globalization of Elections: More Than Just a Local Affair

In the wake of Brazil’s controversial election, many believed the story ended at national borders. But what if the true intent was never limited to Brazil? What if this was just the prototype?

Electronic voting machines, shrouded in secrecy, standardized under the guise of modernization, are now being rolled out across continents. From Seoul to São Paulo, from Manila to Kyiv – a quiet coup is taking place. Not with guns, but with firmware.

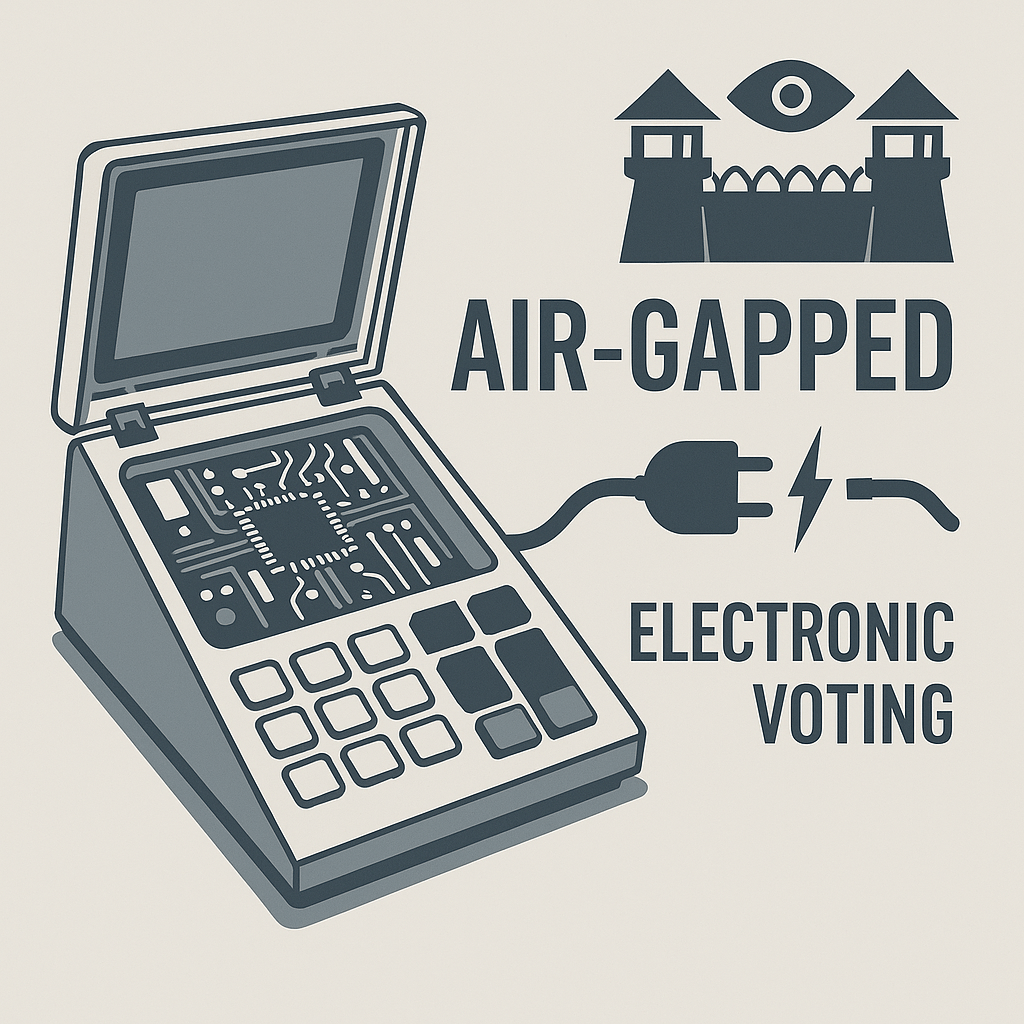

A-WEB & USAID: The Architects of “Global Democracy”

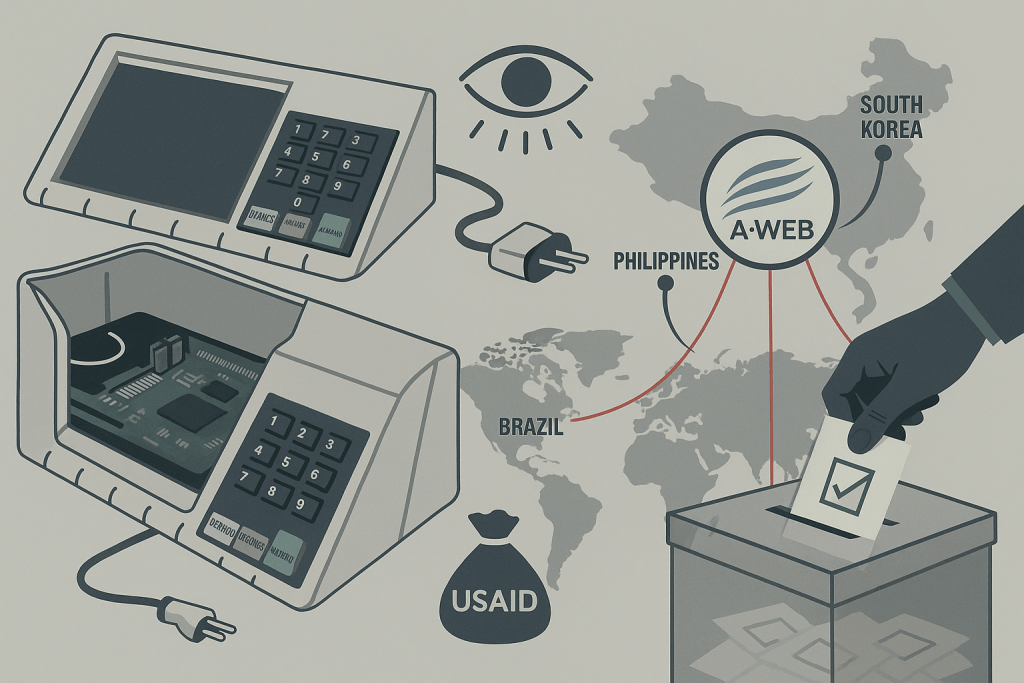

A-WEB (Association of World Election Bodies), headquartered in South Korea, claims to support electoral integrity. Yet it maintains deep ties with regimes accused of voter suppression and opaque systems. USAID, the United States Agency for International Development, offers funding and “advisory support,” shaping election logistics under the banner of democracy.

Together, these institutions embed themselves in national electoral bodies, often under bilateral agreements or memorandums of understanding. Once inside, they introduce technology providers like Smartmatic and Dominion, many of which carry histories of controversy.

Brazil’s TSE (Superior Electoral Court) became a blueprint. Not just for how to run an election, but for how to shape narratives, neutralize dissent, and legitimize questionable outcomes with a veneer of international approval.

Technology as a Trojan Horse

Under the promise of efficiency, electronic voting machines have quietly replaced traditional voting methods. But unlike paper ballots, these machines operate in a black box – invisible to the voter, impenetrable to the average auditor.

In Brazil, local experts who demanded transparency in machine auditing were dismissed as conspiracy theorists. In the Philippines, transmission data anomalies raised questions that were never answered. In South Korea, the machines used are built by private contractors shielded from FOIA-equivalent laws.

The question isn’t just who builds these machines. It’s who programs them, who audits them, and who owns the data they collect.

A Coordinated Suppression of Doubt

Perhaps more alarming than the machines themselves is the machinery of censorship surrounding them.

Social media platforms, under pressure from governments and NGOs, now systematically suppress election-related dissent. In Brazil, YouTube channels questioning the election disappeared overnight. In the U.S., Twitter (pre-Musk) was exposed for colluding with government officials to mute hashtags.

Even academic institutions and journalists who attempt to investigate irregularities find themselves deplatformed or discredited.

The End of Local Control

Elections are no longer national affairs. The tools, the observers, the frameworks – all imported, all controlled.

What began as a push for transparency has evolved into a centralized protocol. And in this protocol, your local vote may still be cast by your finger, but it’s counted – and verified – by an algorithm approved in another country.

The Final Vote

Democracy has always depended on trust. Not just in institutions, but in the process itself.

When the mechanisms become too complex to understand, and the voices that question are silenced, the vote remains. But its meaning doesn’t.

Who really counts your ballot?

And who counted on you not to ask?